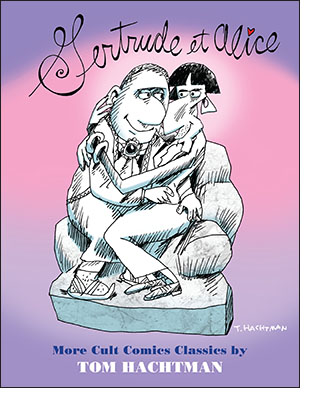

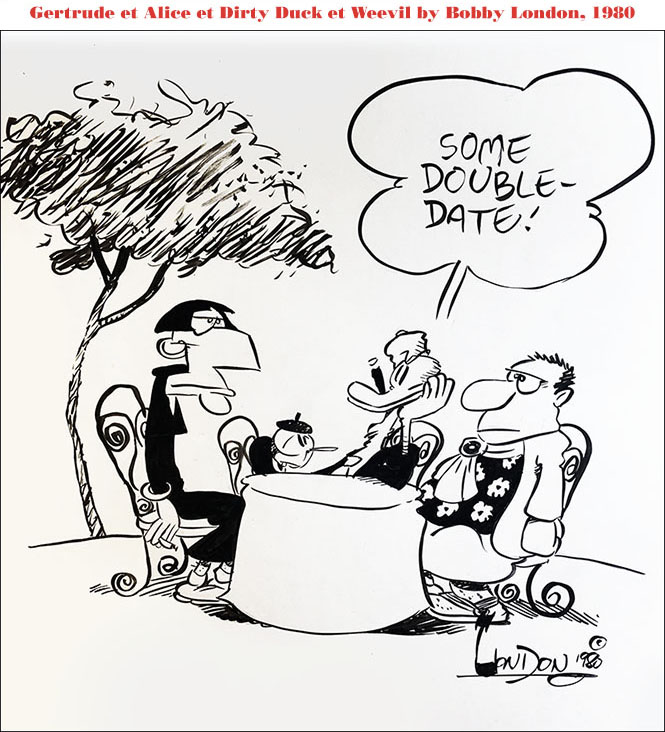

Gertrude et Alice

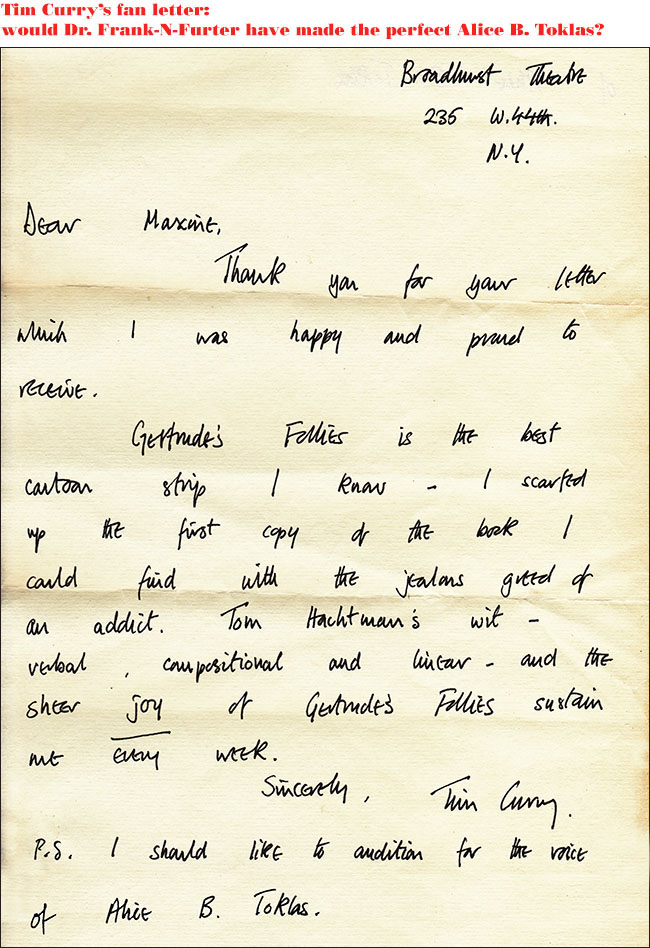

It's Volume Deux of Tom Hachtman's Cult Comics Classic Gertrude's Follies. This full-color collection includes the very best installments from the original run in the Soho Weekly News along with sundry revivals and never-before-published rarities. These utterly unique strips mash up early-century Paris with late-century New York as they explore art, culture, sexual politics, and Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas' singular amour.

It's Volume Deux of Tom Hachtman's Cult Comics Classic Gertrude's Follies. This full-color collection includes the very best installments from the original run in the Soho Weekly News along with sundry revivals and never-before-published rarities. These utterly unique strips mash up early-century Paris with late-century New York as they explore art, culture, sexual politics, and Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas' singular amour.

Krazy Kat meets Janson's History of Art as the endlessly inventive Hachtman toys with the comics form like a pulpy Picasso. The grand dames confront junk food, fad diets, writer's block, vampiric critics, Nazi aesthetes, sycophants, celebs, and Gay Pride Parades, all with the aid of Alice's very special brownies. It's brimming with inspired silliness and an irresistible joie de vivre.

Buy on Amazon

Buy on Barnes & Noble

Buy on Books-A-Million

Buy on Books-A-Million

Buy Volume I on Amazon:

Gertrude's Follies

Order Gertrude et Alice T-Shirts below.

Read Gertrude's Follies online.

Order Gertrude et Alice T-Shirts from Cafe Press!

Paperback • 76 pages • Full Color • 8.5"x11"

On Tom Hachtman & Gertrude’s Follies

by Wanda Corn and Tirza True Latimer

from the Contemporary Jewish Museum Catalog

for 'Seeing Gertrude Stein'

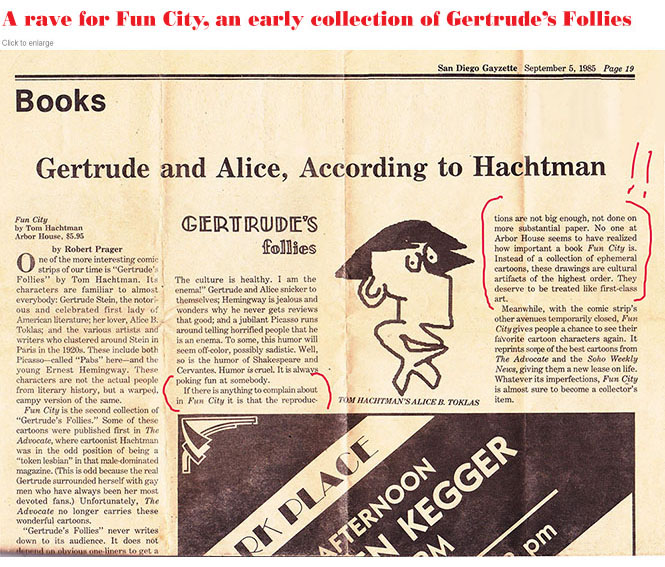

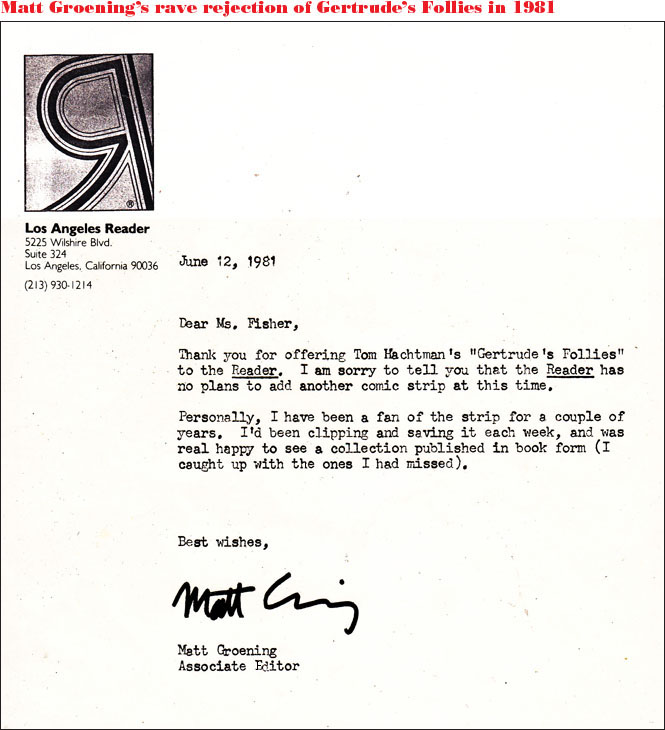

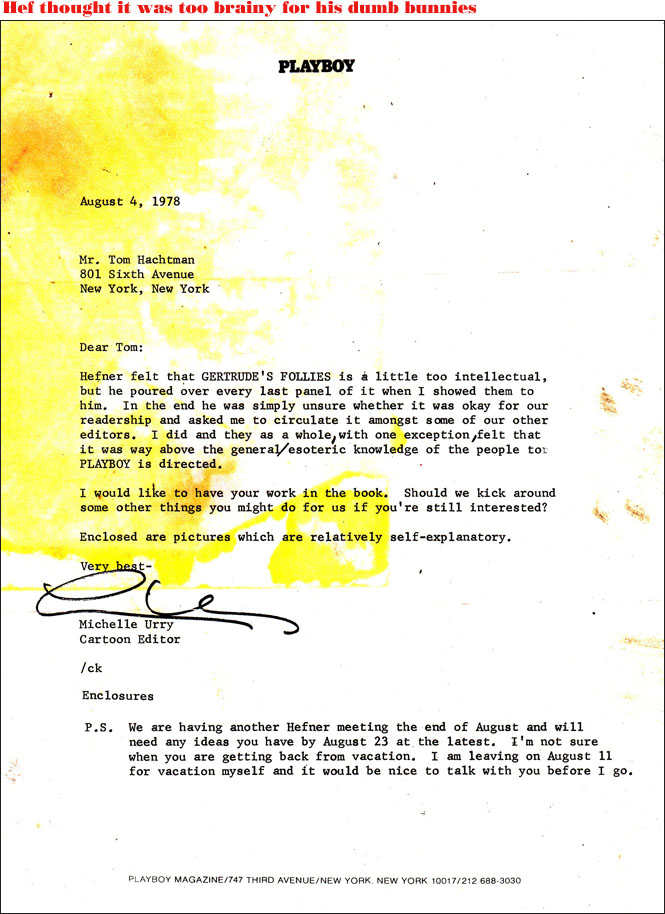

During the period when publications by and about Stein proliferated, and against the backdrop of the women's rights and gay liberation movements of the 1970's, the cartoonist Tom Hachtman began Gertrude's Follies, a comic strip featuring Stein and Toklas. Perusing the Museum of Modern art catalogue Four Americans in Paris: The Collections of Gertrude Stein and Her Family, Hachtman was struck by the Man Ray photograph of Stein and Toklas sitting on opposite sides of the fireplace at 27, rue de Fleurus. "This photograph was in my mind," Hachtman recounts, "when I first thought of doing Gertrude and Alice as a kind of vaudeville comedy couple in a comic strip. I was half asleep. I sat up. I thought of their circle –– Hemingway and Picasso. I knew of Alice and her brownie recipe. I got out of bed and headed for the drawing table with the thought, 'Art, Literature, Marijuana, Homosexuality, Paris, Fun.'" Hachtman's comic strip appeared first in the Soho Weekly News in 1978, and then in the Advocate, the New York Native, the LA Weekly, and the East Village Eye. The collection Gertrude's Follies: An Irreverent Look at the Life and Times of Gertrude Stein and Her Faithful Companion, Alice B. Toklas, was published as a book by St. Martin's Press in 1980. The strip has engendered many spin-offs, such as Hachtman's caricature Gertrude Steinem, which visually and textually collapses Stein into Gloria Steinem, the founder of Ms. magazine. It is one of Hachtman's 'schizographic' images that mere signifiers of two popular celebrities, here Stein in the pose and clothing familiar from Picasso's portrait and Steinem's trademark aviator glasses, straight blond hair, and cigarette. In 2007, Michael Sporn completed the animated short Pab's First Burger, based on Hachtman's strip, and in 2008, two episodes of Gertrude's Follies appeared in 101 Funny Things About Global Warming, by Sid Harris. To this day, the antics of what nowhatmedia.com describes as the "dizzy denizens of the Parisian demimonde" unfold in color online. The legibility and adaptability of Hachtman's comics suggest that his cast of characters has become as much a part of American popular culture as hamburgers.

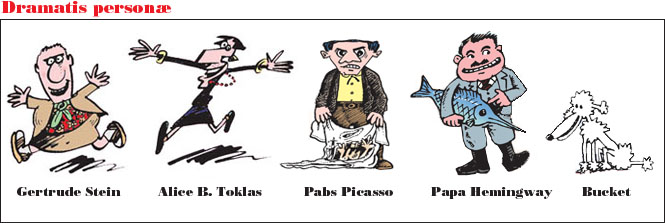

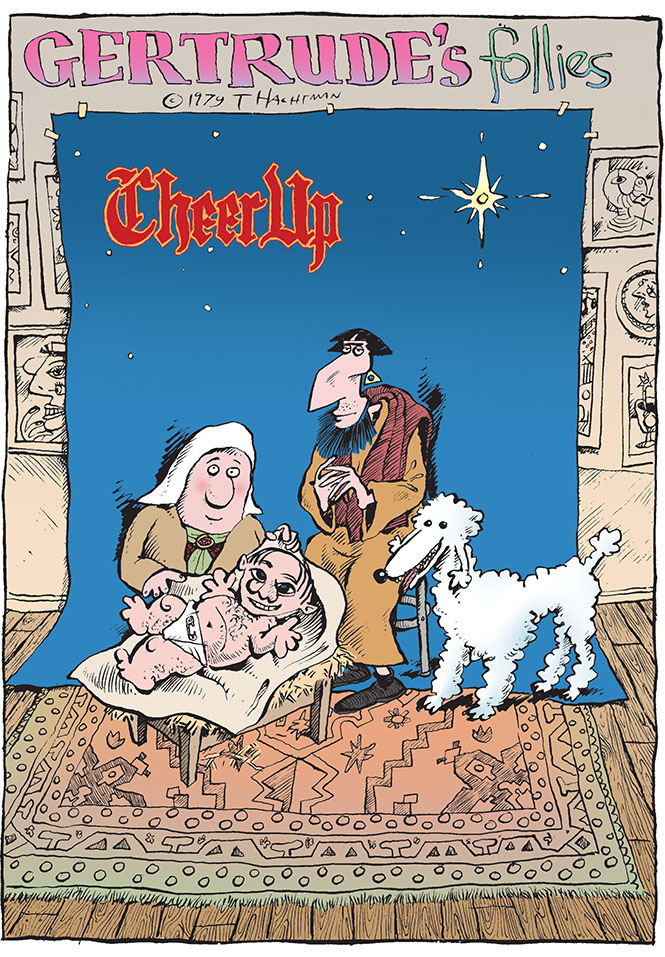

The cartoon Hachtman used as the endpaper for the Saint Martin's compendium –– a manger scene performed by Stein's menage –– lays out all the essentials of the popular myth that his comic strip and its spin-offs embroider. This improbable tableau of Christianity's origin myth stars two lesbians who were also secular Jews: Stein (wearing a feminine wig) in the role of the Virgin Mary and Toklas (sprouting chin hair) in the role of Joseph. Their gaze is fixed on an implied camera –– an audience, posterity. Pablo Picasso, the infant savior, the object of the parental ministrations they mime, squirms in his makeshift cradle. Stein and Toklas's poodle, Basket (dubbed "Bucket" by Hachtman), stands in for the more customary barnyard attendants. The backdrop for this unholy alliance is a suspended bedsheet on which Hachtman has sketched a star to light wise men's passage to the rue de Fleurus salon, where he sets this scene. A few illogical snowflakes dot Hachtman's backdrop, which is otherwise blank but for the injunction "Cheer Up," penned in the pseudo-medieval calligraphy of holiday greeting cards. The frame of Hachtman's drawing exceeds that of the backdrop, allowing the wall of Stein and Toklas's dwelling, densely hung with Picassoesque paintings, to show. The modernist aesthetic evident on these margins resonates purposefully with the pattern of the Persian carpet that serves as a ground for the scene. Like all good send-ups, this cartoon has a basis in fact –– or at least in some received notion of reality. It pictures the birth of modern culture in a symbolically charged nuclear family structure undergoing transformation by its untraditional occupants.

Hachtman's cartoon casts Stein as the "mother" of modernism (personified by Picasso), a role that she herself took pains to elaborate. Lineage is a vexed issue here, owing to the complex sexual identifications and power relations of the principals in the family drama to which Hachtman pays tribute. Although it strains credibility to cast Stein, with her butch bearing, in a maternal role, she could not, with her full bosom, credibly claim paternity. And the hypervirile Picasso, only seven years younger than Stein, wearing diapers and gurgling with infantile satisfaction –– is his role any more believable? Alice, whose gravelly voice and infamous mustache (shaved to a stubble in Hachtman's drawing) support casting her in the paternal role, hardly looks comfortable in it. She was, after all, Gertrude's wife. By the 1970's, this fact was understood well enough so that hachtman could manipulate the codes and his readers would easily still "get it."

As in any successful parody, Hachtman's absurd characterizations ring true in several ways. Under the cover of the joke's self-effacing rhetoric, the cartoon makes a serious point about the relational character of what we call "genius" ( a status that requires recognition). Hachtman's conceit of the holy family, by the same token, illuminates the production of cultural value in a redefined (non-heterosexual) kinship scenario. Specifically, it posits Stein's queer family as an important matrix of modernism. Generally, it pictures kinship itself –– and thus lineage –– as improvised, performative, evolving in negotiation with a symbolic vocabulary and an iconography of family that here fail (or refuse) to cohere. Conceived as a generative web of intentional, affectively, and erotically charged alliances, rather than a biologically determined destiny, the queer "family" offers a conceptual framework for exploring the creative imperatives and constraints of liaisons that resist societal and artistic norms. The drawing captures something essential about Stein's negotiation of a place for herself –– by means of her domestic spaces, performances, images, and queer relations in the public arena and in history.

Hachtman's promotional literature claims that "Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas permanently entered American mythology in 1978 with the advent of Tom Hachtman's brilliant and irreverent comic strip." The truth is, of course, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas entered American mythology much earlier, during Stein's lifetime, and largely as a result of her own and Toklas's efforts. After Stein's death, Toklas (aided by Carl Van Vechten, Donald Gallup, and Thornton Wilder) reached the goal of publishing all of Stein's remaining manuscripts and archiving her remaining papers. These initiatives made Stein available to feminists and gays who were looking for new cultural models in the 1960's and 1970's. By 1978 Stein's myth was so firmly established in the popular imagination that, without knowing just how, Hachtman had absorbed it highlights. He may never have read The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, yet he was able to picture Stein's pre-World War I artistic milieu. He also knew about Toklas's cookbook. "Everyone knows these things," he explained in an interview.

Stein's infiltration of popular genres such as caricature, comics, and movies supports Hachtman's claim that "everyone knows these things." The many photographs and portraits for which Stein posed during her lifetime, the visual "scraps" we have inherited, both provide evidence of and underwrite Stein's celebrity. Cumulatively, these vintage and contemporary images of Stein's work in tandem with literary scholarship, published letters, memoirs, and biographies to confirm the author's status as a figure of cultural and historical importance. And more fundamentally, they convey messages about difference and about the possibility (of even the necessity) of challenging cultural and sexual norms.